Paper Notes

Introduction: Is it effective to shuffle team members project by project?

When working at a startup, chronic understaffing often means teams form and dissolve on a project basis, so member composition never stabilizes. Conversely, in large corporations with few transfers, you work with the same familiar faces day in and day out, with little change.

The Effects of Group Longevity on Project Communication and Performance: Administrative Science Quarterly is a paper that examines how group tenure (the average length of time members have worked together) in R&D projects affects communication behaviors and technical outcomes (performance).

Though it dates from 1982, many of its insights still hold true today, so let’s unpack it.

Background: The hypothesis that verbal, face-to-face communication is a key information channel

The paper assumes that in engineering fields, verbal and interpersonal communication is a more powerful means of transmitting information than reports or journal articles. With the rise of the internet, this balance may have shifted somewhat.

Past studies (at the time) showed that while increased internal communication boosts project outcomes, interaction with external experts has mixed effects depending on project characteristics.

The hypothesis: as group tenure lengthens, teams become more inward-looking and isolated from external information.

Study Sample: major U.S. corporation’s R&D facility

They measured 50 project groups (each with 3–15 members) at a large U.S. company’s R&D labs.

They assessed how communication within the project, within the division, within the lab, across the organization, with external experts, and with vendors influenced performance. Performance was rated on a seven-point subjective scale by division heads and lab directors.

Group tenure was defined as the average individual tenure on the project, then categorized into 0–1.5 years, 1.5–4.9 years, and 5+ years for analysis.

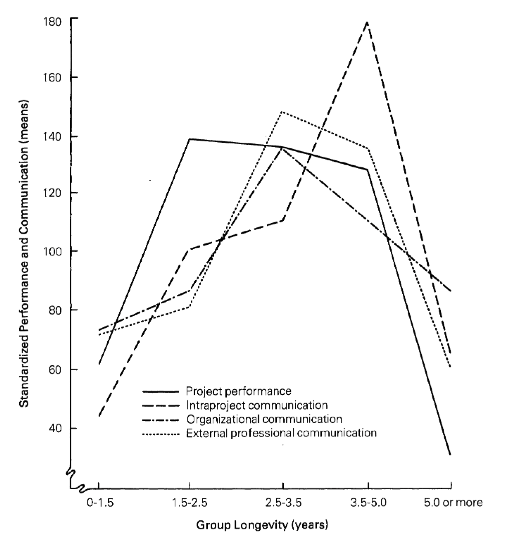

Results: Performance peaks at 2–4 years of tenure

The results reveal a clear hump-shaped curve, with performance peaking when tenure is 2–4 years. Teams with tenure under 1.5 years or over 5 years showed significantly lower performance.

Long-tenured groups exhibited reduced communication within the project, with other departments, and with external experts. Communication within the division, within the lab, and with vendors showed no significant differences.

This supports a model of long tenure → reduced communication → lower performance.

Countermeasures: How to boost motivation in long-tenured teams

Long-tenured groups showed signs of Not-Invented-Here (NIH) syndrome—believing their own methods are best and becoming insensitive to new information.

To counter this, the authors recommend monitoring average tenure per project and periodically assigning external or new members to teams with over five years’ tenure to disrupt fixed mindsets and revitalize communication.

Supplement: Subsequent research & personal reflections

Subsequent studies have argued that even long-tenured teams can stave off performance declines if points of contact with external sources are deliberately engineered. Indeed, some companies send entire teams to conferences or training workshops for precisely this reason.

On the other hand, Brooks’s Law—that adding people to a late software project only makes it later—remains unrefuted. The inefficiency inherent in constantly forming and dissolving project-based teams is unchanged, and it’s important to bear in mind that it takes time for a team to stabilize.